The event brought together researchers, trade unionists and representatives of public institutions from five partner countries: Austria, Belgium, France, Poland and Spain.

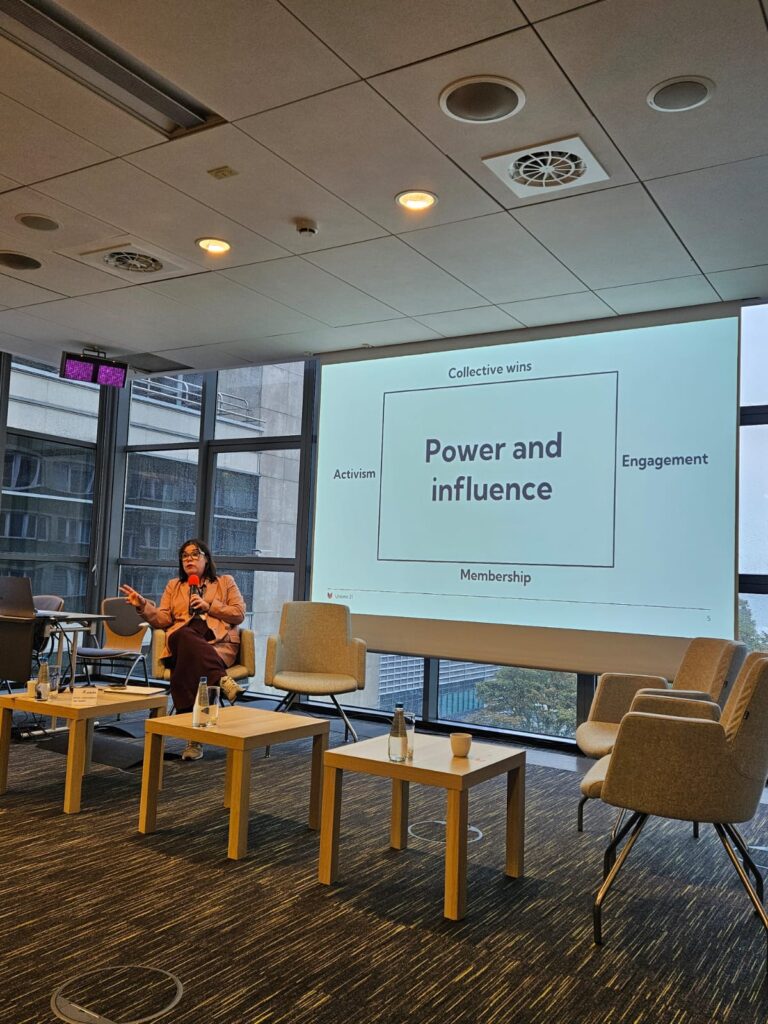

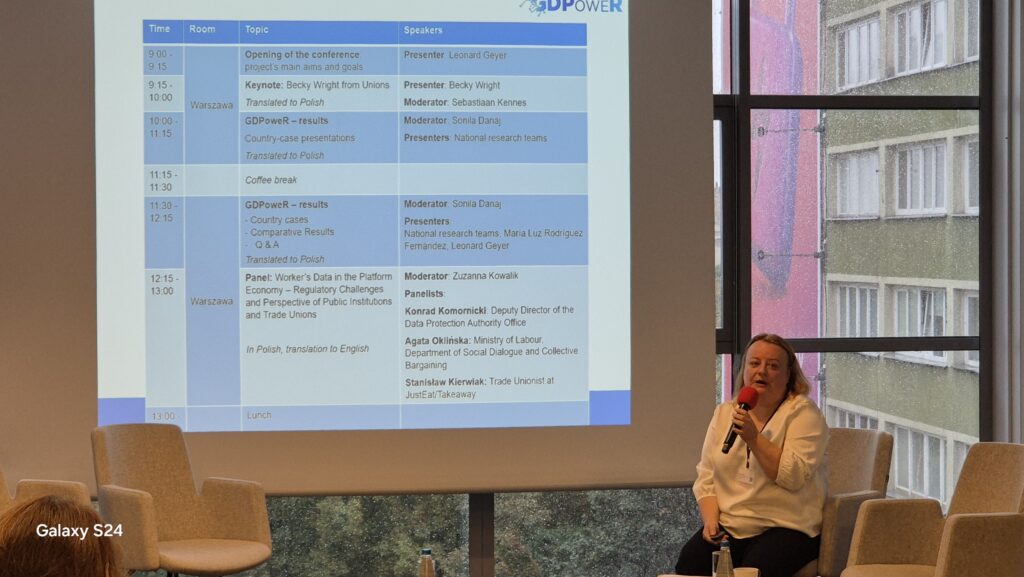

Keynote: How can unions represent atypical workers?

The highlight of the opening was a speech by Becky Wright, director of Unions 21. Her presentation focused on the challenges facing trade unions in representing atypical and dispersed workers, including those employed in the platform economy.

Wright emphasised that unions must answer two fundamental questions:

- How can we represent today’s workforce and tomorrow’s workforce?

- How to remain relevant in the digital age?

The answer lies in openness, flexibility and building new forms of engagement. Wright identified five key pillars of union effectiveness that shape its influence and power: activism, shared victories, engagement and membership. In her view, these elements will determine whether unions can effectively represent the growing group of atypical workers – from couriers and app drivers to YouTubers and other self-employed people in emerging professions.

Research results: national case studies

The rest of the conference was devoted to presenting the research results conducted by national teams.

- France: Cynthia Srnec from Sciences Po Saint-Germain-en-Laye and the THEMA research institute drew attention to the rapid growth of the delivery and transport market (Uber Eats, Deliveroo, Uber), but also to the poor quality of employment, the lack of transparency of algorithms and the weakness of the new ARPE institution, which was supposed to support social dialogue. Low turnout in employee representative elections (only 3.9% in deliveries) undermines the legitimacy of the ARPE-based system. Effective regulation in France requires a binding legal framework, transparent algorithmic practices and inclusive representation covering workers with uncertain residence status.

- Poland: Zuzanna Kowalik from IBS highlighted the lack of collective agreements and the dominance of fleet intermediaries, which blur platforms’ responsibility towards drivers and couriers. The only clear example of grassroots mobilisation is the trade union organisation at Pyszne.pl. The data collected by platforms remains opaque, which exacerbates workers’ feelings of surveillance and powerlessness.

- Austria: Leonard Geyer from the European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research showed that Austria has successfully negotiated collective agreements for bicycle couriers and taxi drivers, and two large companies have works councils. However, platforms circumvent regulations by working with self-employed persons and independent contractors. Data analysis shows that although no violations of agreements have been detected, circumvention of the law remains a problem.

- Belgium: Laurene Thil discussed the Belgian legal system, which is complex and inconsistent, with platforms employing various strategies to avoid regulation. The study found that workers have difficulty accessing their data, fearing reprisals for submitting requests under the GDPR. Organisations such as La Maison des Livreurs have become a key source of support and mobilisation.

- Spain: Jesus Cruces Aguilera’s presentation showed that although the country has a relatively developed regulatory framework – including the famous Ley Rider of 2021, which introduced a presumption of employment for couriers – implementing these regulations remains problematic. Platforms continue to exploit legal loopholes, particularly through outsourcing and subcontracting. A strategy used in Spain is strategic litigation to enforce the recognition of an employment relationship.

Comparative perspective

In the summary session, María Luz Rodríguez Fernández presented a comparative report. She pointed out that despite different regulatory traditions, similar challenges arise in all countries: opaque algorithms, low social security and difficulties in enforcing negotiated agreements.

Content of agreements: classic issues are covered, algorithms still marginalised

Most agreements regulate ‘classic’ issues (working time, pay). Exceptions include Just Eat in Spain (right to disconnect, privacy, transparency of algorithm parameters, algorithm committee) and the now expired. Foodora agreement in Austria. The report highlights the importance of Article 25 of the PWD, which encourages EU countries to negotiate on the classification of workers and algorithmic management.

Access to data under the GDPR: fear, barriers, poor-quality responses

In all countries, respondents faced similar obstacles when submitting GDPR requests: fear of retaliation, complex procedures, and, on the part of companies, refusals or inadequate responses (especially regarding Article 22 on automated decision-making). Where data was provided, its quality was uneven: in ride-hailing, often only scans of documents were provided; for couriers, there were large differences between platforms (Glovo—fragmentary PDFs; Just Eat/Pyszne.pl—detailed CSV files with payments, rates, and contract variables).

What platforms really collect and how employees feel about it

Most of the respondents know that they are being monitored, but have a vague idea about the details and logic of the algorithms – this creates a sense of surveillance, loss of autonomy and frustration with opaque decisions. At the same time, some people see the use of data (e.g. tax calculations, defence against unjustified complaints). Data rarely initiates mobilisation, but it becomes fuel for dispute after a ‘spark’ (e.g., account blocking).

Enforcing agreements: easier with working time than with algorithms

Traditional provisions (rates, standards, breaks) can be verified and generally work. The most challenging thing is what is key to platform work: data processing and algorithmic management. Here, the report sees potential in using employee data for compliance monitoring – and a research gap in employee-intermediary relations.

Conclusion from the comparison

Without absolute transparency of algorithms and the inclusion of ‘excluded’ groups (self-employed, working through intermediaries) in negotiations, even the best arrangements will only work partially. The transposition of the PWD and transparency obligations on the part of platforms can be a lever. Still, enforcement and including employee data in negotiation practice will be key.

Institutional panel

During the panel discussion with representatives of the Personal Data Protection Office, the Ministry of Labour, and the trade union, the participants discussed how regulations—including the EU Platform Work Directive—can realistically change workers’ situations. The participants agreed that enforcing the law and creating mechanisms for workers’ and their representatives’ access to data will be crucial.

The Director of the Social Dialogue Department at the Ministry of Family, Labour and Social Policy, Agata Oklińska, announced that work is underway to transfer collective agreements from the Labour Code to a separate act. This is intended to facilitate negotiations for people employed on civil law contracts and the self-employed. This change could significantly improve the situation in Poland, where less than 15% of employees are covered by collective agreements – one of the lowest rates in the European Union.

Konrad Komornicki, Deputy President of the Personal Data Protection Office, emphasised that the UODO was established to protect citizens, and any abuse by employers – including platforms – should be reported as a complaint.

Stanisław Kierwiak from the trade union at Pyszne.pl pointed out that employees eagerly await regulation changes that will allow trade unions to better control algorithm operation. An opportunity for this may be the transposition of the Platform Work Directive, which goes further than the current GDPR provisions regarding employee data protection.

The discussion also raised the question of implementing the Omnibus package, which, as the employees pointed out, may be perceived as a threat to the rights already secured under the GDPR. However, both the representative of the UODO and the Ministry admitted that this issue falls within the competence of the Ministry of Development and were unable to provide a clear answer to the participants’ concerns.

Sessions of scientific articles presented by participants

During the afternoon session in Warsaw, researchers gave ten presentations that showed the different faces of the platform economy in Poland and Europe.

The first to speak was Dominika Polkowska (UMCS), who presented Poland’s most extensive socio-demographic study of couriers and app drivers. The results showed the enormous diversity of this group – almost half are migrants, and the valued flexibility does not exclude widespread financial dependence on platforms and low income satisfaction.

Next, Kseniya Homel (Centre for Migration Research, University of Warsaw) presented the results of interviews with migrants working in food delivery. Their stories revealed a web of uncertainties related to the labour market and residence status, including dependence on fleet intermediaries and experiences of discrimination that deepen their sense of exclusion.

The following presentation, prepared by Karol Muszyński (University of Warsaw), focused on how product market regulations affect platform working conditions. A comparison between Poland and Italy showed that local platforms (e.g. Stava, Mymenu) can exploit market niches to offer more stable employment, while international giants resort to cost-cutting strategies.

In his speech, Aleksandar Kovačević (University of Belgrade) addressed the topic of the digitalisation of work and its significance for older workers. He emphasised that platforms can be both an opportunity to extend working life and a source of new inequalities – for example, in the case of Uber drivers, older drivers earn less because they are more likely to work on the outskirts of cities and have difficulty using the app.

The session closed with a presentation by Cynthia Srnec, who compared the regulatory models of Spain and France. They pointed out that the Spanish Ley Rider law gave workers a stronger legal basis than the French ARPE system, which suffers from low turnout and a lack of real bargaining power, proving that the design of institutions determines who has the upper hand in disputes with platforms.

At the same time, a second session was taking place in the next room.

The first speaker was Marta Otto (University of Warsaw), who pointed out that current data protection regulations – based on the individual enforcement of one’s rights – are insufficient in the face of the collective effects of algorithmic management. She emphasised that the Platform Work Directive offers an opportunity to strengthen collective oversight and the right to digital co-determination if Member States support trade unions in acquiring the competence to audit algorithms.

Next, Anne Joppe (University of Utrecht) presented a legal analysis indicating that the proposed platform directive could remedy the GDPR’s shortcomings regarding protection against automated management. Her presentation highlighted the tension between formal privacy protection and employees’ practical lack of influence on algorithmic decisions.

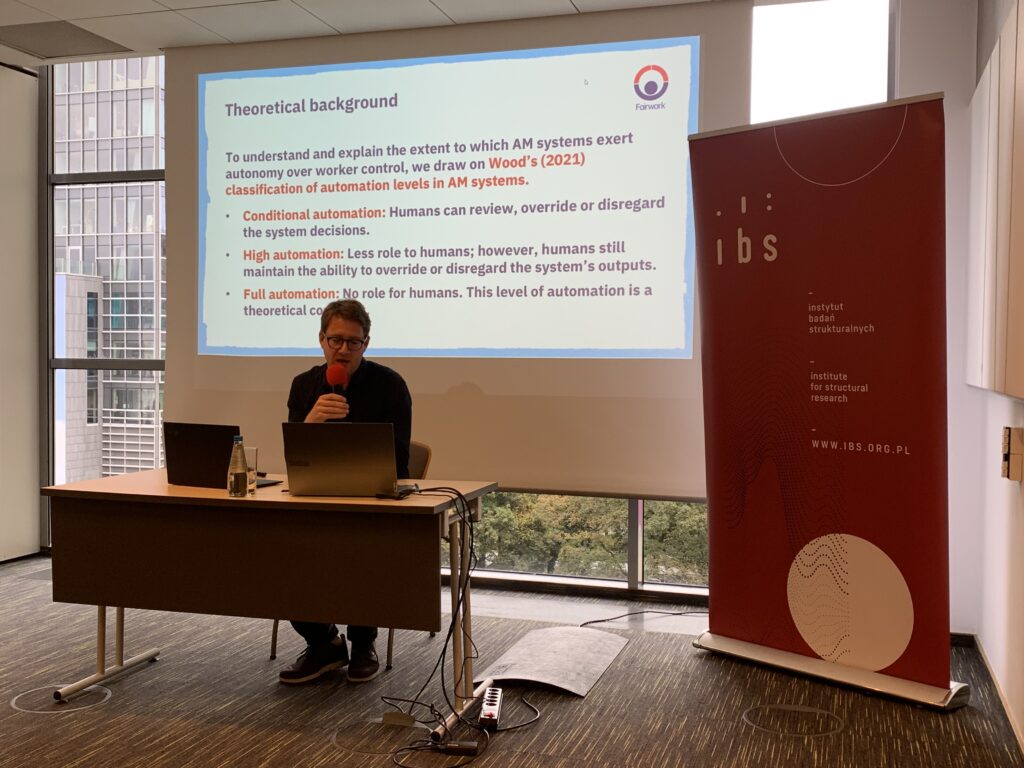

The following presentation, by Tobias Kuttler and the team from WZB, took the audience to Germany. Based on 56 interviews with drivers and couriers, the researchers showed that the level of automation varies between platforms, and appeal mechanisms often exist only on paper – real human involvement in decisions serves the interests of companies rather than employees.

Joanna Bronowicka (European University Viadrina) spoke about innovative technical testing methods for employee applications that reveal what data platforms collect. Her team showed how cooperation between data protection authorities, trade unions, and IT experts can effectively challenge illegal practices—an example of this was the record fines imposed on Glovo in Italy. We will be organising a workshop with Joanna and people working for Polish platforms at our Institute at the end of October.

The session closed with a presentation by Leonard Geyer (European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research, the institution coordinating GDPoweR), who addressed the impact of algorithmic surveillance on the well-being of employees. The results of focus groups from Austria, Poland and Belgium showed that workers live in the shadow of opaque system evaluations, which causes stress, a sense of injustice and fears of account deactivation – effectively discouraging mobilisation and unionisation.

The GDPoweR conference in Warsaw showed how multidimensional the challenges of platform work are – from legal and institutional regulations, through barriers to data access, to the psychological costs of algorithmic surveillance. At the same time, the event confirmed the growing role of scientific research and cooperation between trade unions, regulators and technical experts in the fight for transparency and fairness in the digital economy. For participants from eight European countries, it was an opportunity not only to summarise the two-year project, but also to outline directions for further action – so that the digital transformation of the labour market does not mean the erosion of rights, but new opportunities for their adequate protection.